Introduction

With the increasing density of urban development being encouraged by government, it is more important than ever that the available land bank be efficiently used. This includes maximising the value provided by green space in developed and developing areas.

Linear parks containing a waterway, in particular, offer a high degree of visual amenity and a substantial improvement to the overall urban scape.

Typical urban ephemeral waterways carry flows only during and shortly after rain events. The catchment drainage purpose of an urban waterway therefore occupies only a very small component of available time. For the vast majority of the time, the space is available for a full range of urban community recreation and amenity purposes.

When using such corridors, the community does not typically distinguish between ‘open space’ and ‘drainage corridor’. By contrast, most Local Authority planning schemes clearly separate the two and most do not allow infrastructure offsets for open space along ‘drainage corridors’.

A developer dedicating drainage reserve without any recompense will, naturally, dedicate the minimum possible area.

To fully realise the multiple urban benefits of green spine linear corridors Local Authority planning we need:

- Change to Local Authority planning schemes and focus,

- Proper valuation of green space, and

- Re-prioritisation and focus of subdivision designers.

This paper illustrates the results that can be achieved when a Local Authority is prepared to step outside its comfort zone and work with designers who focus on green space opportunities ahead of subdivisional yield.

The Site

The project site covers two adjoining, but separately owned, properties traversed by several significant ephemeral waterways situated in the upper headwaters of Spring Creek. Spring Creek generally flows west, draining the broader Glenvale precinct.

During the course of undertaking flood studies for the adjoining landholders (under separate engagements) as part of preliminary work leading to Development Applications, the engineers (RMA) realised the site presented an opportunity for a modern approach.

The site is a beautiful natural setting consisting of a myriad of landscape types rich with habitat and recreational opportunities. It could form an integral component of the future community, providing a richness of open space provision and a functional environmental asset of a creek and wildlife corridor.

After gaining in principle agreement from the two landowners, RMA approached Council. Timing is everything and the engineer’s approach coincided with advance planning commencing in Council’s Strategic Planning section.

Council’s planning team were keen to explore the results that might be achieved if open space planning was re-focused and traditional parks and drainage planning codes were re-thought.

Planning Background

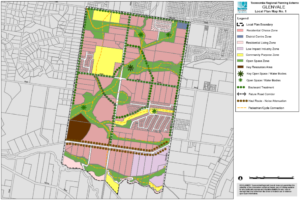

The site is situated within the growth area identified in the Glenvale Local Area Plan to Toowoomba’s western edge. It forms the future residential edge before transitioning to rural-residential zoning.

The Local Area Plan was developed in 2011 and identified an open space corridor that focussed on the local creek system. There were a number of functions applied to this open space in the local area plan including drainage and active transport connections.

Clearly, however, the corridor was a key component in the provision of recreation parkland for the new community at Glenvale. It could balance an otherwise low provision of green open space to this western region, with generally small and disconnected spaces allocated.

How this linear corridor, that was to be all things to all people, would be delivered was not within the scope of the Local Area Plan. In that context, conflicts between engineering standards and design elements of the many functions only become clear when it comes time to deliver on the strategic intent of a particular site.

Council had been working on a Framework for the delivery of Open Space that has multiple functions, and a review of Council’s standards and open space policy. The Glenvale parkland opportunity came at a time when Council’s strategic planners were looking for a pilot to test the waters.

Overall Approach

Team

A project team was set up involving:

- key stakeholders from several Council departments (Planning, Development Assessment, Parks, Drainage),

- civil and hydraulic engineers, RMA Engineers,

- environmental consultant, Redleaf Environmental, and

- urban designers, Lat27.

Site Inspection

A detailed site inspection was undertaken by the whole team. It was quickly apparent to the group as a whole that the site was a perfect choice to investigate how future residential development might incorporate multi-use open space.

Environmental Study

Following the site inspection, Redleaf Environmental undertook a desktop review of available vegetation and fauna data and mapping followed by a detailed field assessment.

The field assessment included specific identification and GIS location mapping of features of environmental significance.

Hydraulics

After agreeing hydrologic analysis parameters with relevant Council engineers, 2D hydraulic modelling was undertaken by RMA to identify existing natural flood extents.

In order to maximise the urban scape benefits of the green corridor, it was intended that the natural stream behaviour be maintained. That is, there was to be no artificial narrowing of waterway corridors to increase the area of developable land.

To put the relative importance of the catchment drainage and urban community recreation purposes into context, flow magnitude and duration information was extracted from the hydrologic model.

The northern waterway is the larger of the two catchments which drain through the site. The waterway carries reasonably large flows (nearly 120 m³/s for the 1% AEP event) during storms.

Like other catchments in the Toowoomba urban area, . Flow development and duration times are also therefore short.

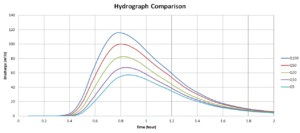

Figure 1 below illustrates the modelled hydrographs and flow times for various standard AEP design events.

It can be seen that typical flow events last about two hours or so.

There are approximately 4410 daylight hours in Toowoomba in a year.

Adopting a typical flow event duration of two hours, the 20% AEP (one in five year) event occupies approximately 0.01% of daylight hours, the 10% AEP event occupies 0.0045% and the 1% AEP event occupies 0.0005%.

The hydrograph comparison also shows that, for example, flows in the large 1% AEP (one in 100 year) event exceed the level of the 20% AEP event for only about 40 minutes.

Clearly then, the catchment drainage purpose of this waterway, whilst important, occupies only a very small component of available time. For the vast majority of the time, the park is available for a full range of urban community recreation purposes.

Planning context

Council Staff had the opportunity to meet with the consultant team to articulate the intent of the local area plan including parks requirements, access paths and other design standards relevant to the delivery of public infrastructure.

Urban Design

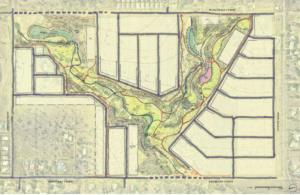

With environmental and hydraulic constraints identified and mapped, urban designers Lat27 developed initial concept plans for multi-use open space along the waterway spines. The initial concept included a preliminary subdivisional layout.

Workshops and Iteration

Concept plans were workshoped by the team over several iterations.

Key issues identified by the team in developing a workable model included:

- waterway health improvement,

- restoration and maintenance of the environmental corridor,

- activating the waterway to connect people with their creek and nature,

- managing flood risk and damage, and

- minimising maintenance regimes.

Concept Master Plan

The final concept master plan included six precincts:

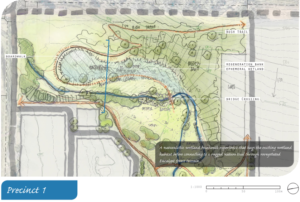

Precinct 1: A naturalistic wetland boardwalk experience that hugs the existing wetland habitat before connecting to a rugged nature trail through revegetated Eucalypt forest terrain.

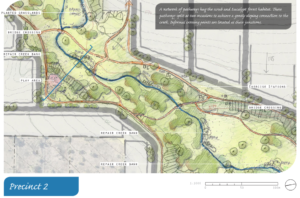

Precinct 2: A network of pathways hugs the scrub and Eucalypt forest habitat. These pathways split at two occasions to achieve a gently sloping connection to the creek. Informal crossing points are located at these junctions.

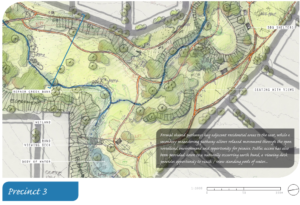

Precinct 3: Formal shared pathways hug adjacent residential areas to the east, while a secondary meandering pathway allows relaxed movement through the open woodland environment and opportunity for picnics. Public access is provided down to a naturally occurring earth bund, a viewing deck provides opportunity to reach or view standing pools of water.

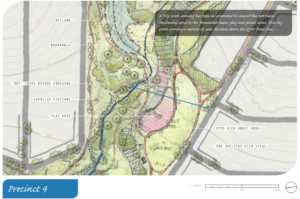

Precinct 4: A ‘dry’ creek crossing is incorporated to connect the northern residential areas to the formalised lawn, play and picnic areas. This dry creek crossing is outside of, and elevated above, the Q100 flood line.

Precinct 5: A naturalistic wetland boardwalk experience hugs the existing wetland habitat before connecting to a ‘dry’ creek crossing and the formalised lawn, play and BBQ areas west.

Precinct 6: A fish rock ramp is installed adjacent to the existing weir to allow fish species to make their way downstream.

The master plan included consideration of escape routes . . .

. . . . and maintenance hierarchy.

Concluding Thoughts on This Project

Once green space is lost, it is lost forever.

Overcoming barriers to the multiple use of open spaces is critical if the community is to maximise the efficient use of ever shrinking green areas in our urban communities.

The case study in this paper demonstrates the improved urban scape that can be achieved when multiple use considerations are applied to an area which, under current codes, would be de-valued as ‘drainage reserve’.

Effective planning and team work in a cooperative environment (Council, environment and design professionals) can achieve a superior result for all parties (community, Council and developer).

The project delivered a ‘best practice’ exemplar for future residential development and multi-use open within the Toowoomba Region which:

- satisfied the hydraulic requirements of the waterway, whilst

- simultaneously and positively enhancing the broader urban scape, by

- building on the existing fabric of mature vegetation and landform, and

- activating connectivity and community interface with the waterway.

Development applications over the project area are yet to be submitted to Council. Whilst the project is still a paper concept, both Council and the landowners are keen to see it achieve reality.

Subsequent Finalisation of Council’s Framework for the Delivery of Open Space

Using this and several other test projects, Council (assisted by a group of specialist consultants) subsequently workshopped and refined a formal Framework to guide the delivery of Multi-Use Open Space into the future.

The Framework has since been accepted by Council as an example of how collaboration, communication and innovation can result in better, more sustainable outcomes for the Toowoomba Community.

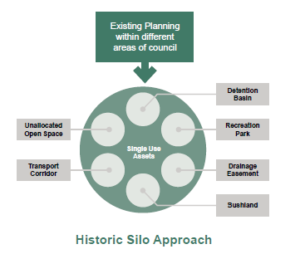

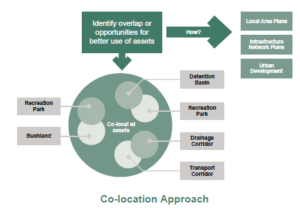

Council has evolved from an organisation that planned and delivered infrastructure in silos, often with ugly results, to an organisation that understands the efficiency benefits of colocation and a focus on seamless integration.

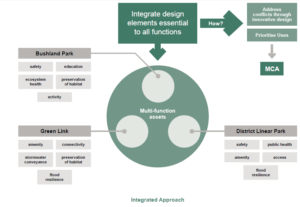

The key to this new approach is the input or communication of technical data in a way that other stakeholders understand and can respond to. Another learning from the Glenvale Parkland project was the need for prioritisation of design elements into ‘essential’ and ‘nice-to-have’ or negotiable and non-negotiable elements in the context of site-specific project objectives.

None of these multi-use open space projects will have out of the box solutions. They need flexibility and focus, by all parties, on the outcomes as opposed to the inputs.

Credits

- Project Team

- Toowoomba Regional Council.

- RMA Engineers (civil and hydraulic engineering).

- Lat27 (urban design).

- Redleaf Environmental (environmental).

- Imagery and illustrations (with permission) from:

- Glenvale Linear Parkland Concept Design Report (Lat27, Nov 2015).

- Glenvale Linear Parklands – Environmental Study for Green Space Infrastructure Planning (Redleaf Environmental, Aug 2015).

Framework for Multi-function Open Space (Lat27, July 2016).